One of the most frequent questions I am asked as I prepare for this trip is, “what are you bringing in order to call for help?” I will have several different communication devices, and I think of them in two main categories, “on the water” and “on shore.” Having multiple options in each category provides some redundancy and an extra margin of safety. This is important to me due to the increased risk of a solo trip in the stormy season. Below is a list of what I am bringing and why.

My signalling and communication kit.

On-Shore Equipment

Cell Phone: While I do not expect to get a signal in the remote areas of the coast, there are quite a few towns along the way. I should be able to rely on the phone as a means of non-emergency communication periodically. I may also be able to use the data connection to update this blog!

Garmin InReach: This is a GPS unit with the added ability to communicate via text message through the satellites, providing for another avenue of non-emergency communication. It also has an SOS beacon, which allows me to broadcast my location and call for help from anywhere.

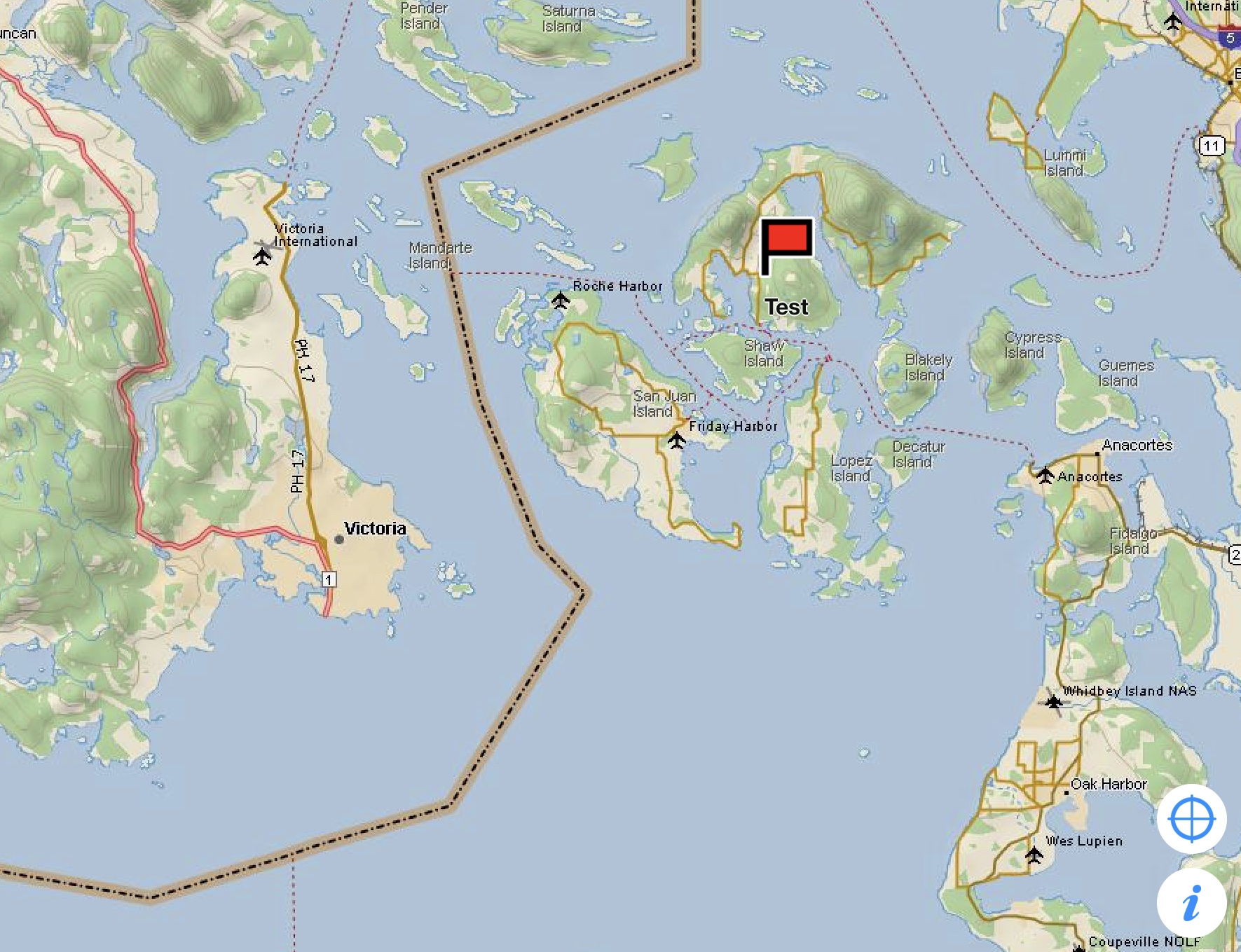

The InReach has one last feature that I will probably use the most: I can send my location to be marked on the map that is linked to this website. This can be a fun way for people to follow along with how the expedition is progressing. It also adds another layer of safety by providing a “last known location.”

Showing my location on the InReach website.

On-Water Equipment

VHF marine radio: Kayakers will be familiar with this piece of gear, a two-way handheld radio that is waterproof and floats. I can keep it in a pocket as I paddle and use it on the water to call the coast guard and communicate with other boats. One of the most useful features of this is radio is the weather band. These special channels provide constant weather forecasts for the surrounding areas, including information about pressure systems moving onshore from out in the Gulf of Alaska. Having good weather forecasts will be key to deciding when to paddle and when to stay in my tent sipping hot tea.

Personal Locator Beacon (PLB): This is one I hope to never use. It is a plastic device about the size of an old flip phone and will be in my chest pocket whenever I am on the water. My beacon is registered with NOAA in my name and phone numbers for emergency contacts. When activated it sends out a one-way distress signal to a group that monitors distress signals from all marine vessels world-wide. They will relay that signal to the Canadian search and rescue teams. The signal is one-way and has only one message, “HELP!!! NOW!!!” This is only to be used in cases of life-threatening emergency: if I activate it something drastic has happened and the trip is over.

Non-Electronic Signals: These include whistles, a small fog horn, a strobe light, bright red flares, a parachute flare, and day-time orange smoke flares. These are all part of the standard signalling kit a kayaker should have along when heading out in advanced waters. While these are not effective means of summoning outside help on their own, each can be crucial for helping rescuers find you as they get closer to you position.

Firing off old flares at the Lumpy Waters symposium in October.

I have acquired most of this gear bit by bit over the past few years, adding additional layers to the system as the trips I undertake have become more ambitious and remote. For this trip I am making sure I have multiple emergency and non-emergency communication options. The goal again is to have redundancy, so if one system fails another can be used in a similar way. While I only plan on using the non-emergency communication devices, it does give me peace of mind to have the others along and know that I can call for help from anywhere.

That said, I still feel strongly that I have to focus on careful risk assessment each day and not putting myself in dangerous situations. The reality is that even if I triggered a beacon, it would be hours before someone arrived. Hours is a very long time when you are out on the ocean in a small boat. That means I have to always be able to rescue myself while on the water, and know when to not head out. I will be focusing on both of those topics in future posts.